Poor Man's Chest Seal

Defibrillation pads make excellent improvised non-vented chest seals when responders find themselves without access to purpose-built devices. Has this technique been mentioned in medical literature and is there anything to support it?

Penetrating trauma of the thorax which creates an injury pattern where air is exchanged between the environment and pleural space through the wound is treated emergently with an occlusive dressing.[1,2,3] Wounds such as these are referred to in literature by a handful of names, including: open pneumothoraces, open or sucking chest wounds, and communicating pneumothoraces. Initial care focuses on preventing the communication of air through the wound and to the pleural space. This can be rapidly accomplished by placing a gloved hand over the injury, preferably during the patients maximal exhalation.[8] The next step depends on what equipment and training a given provider has available to them.

Current Practice

Many textbooks and guidelines recommend three-sided occlusive dressings, while the forefront of treatment has moved to purpose-built devices. The 2022 Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines state:[2]

All open and/or sucking chest wounds should be treated by immediately applying a vented chest seal to cover the defect. If a vented chest seal is not available, use a non-vented chest seal.

Developed by the Department of Defense Joint Trauma System, Center of Excellence, TCCC has the advantage of knowing what equipment military medical personnel have access to. However, civilian EMS training and access to equipment vary widely. StatPearls review of current literature pertaining to prehospital pneumothorax notes:[1]

There are multiple treatment modalities available for use by prehospital providers with varying use by both levels of training and geographic location. No single accepted method is being performed on a national level. (emphasis added)

Because of this, many EMS professionals find themselves without purpose-built devices and only the recommendation to create a three or four-sided occlusive dressing.[8] In practice these three-sided occlusive dressings are impractical; as noted in several resources such as Treating Sucking Chest Wounds and Other Traumatic Chest Injuries published in the Journal of Emergency Medical Services (JEMS):[3]

Early treatment of a sucking chest wound included placing an air-occlusive dressing over the site and taping it on three sides. It was thought that this dressing prevented additional air from entering the pleural cavity during inhalation and allowed trapped air to escape from the untaped edge during exhalation. However, the time required to apply this dressing and the limited effectiveness of the adhesive to stick to a diaphoretic bleeding patient often resulted in dressing failure. (emphasis added)

The same StatPearls article that noted the varied treatment modalities for communicating chest wounds in civilian EMS later states:[1]

Concerns about the time required to place the dressing and difficulty with properly taping it to the chest have led to the development of other techniques and commercially available devices.

The Critical Care Transport textbook produced by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and endorsed by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP); the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UBMC); and the International Association of Flight and Critical Care Paramedics (IAFCCP), in the section on Open Pneumothorax reads:[8]

Of note, debate exists regarding the most appropriate means of achieving an occlusive seal over an open chest wound. Regardless of the method employed, the objective is to achieve an occlusive seal and prevent or relieve subsequent pressure buildup. (emphasis added)

They go on to recommend taping an occlusive dressing on three or four sides while stressing the importance of careful monitoring of these patients by providers. This effectively leaves EMTs, paramedics, and other professional rescuers employed by agencies that do not stock purpose-built chest seals to improvise.

The Best Improvisational Tool Available

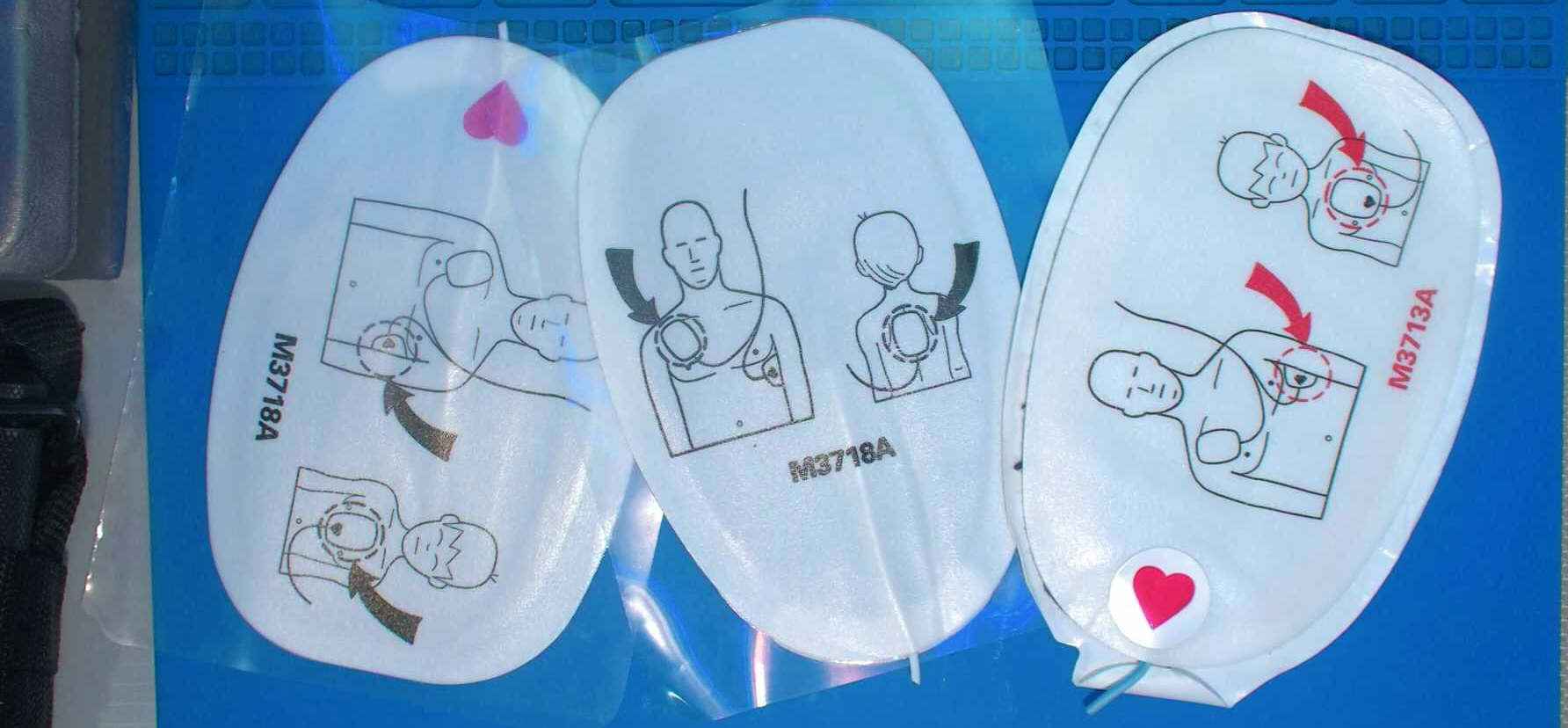

A defibrillator pad works nearly identically to a non-vented chest seal and is available to most professional rescuers. While there doesn't appear to be any research into their effectiveness as chest seals specifically, they are mentioned sporadically in publications as an alternative to the ineffective three-sided dressing. The same JEMS article mentioned above goes on to state:[3]

An alternative approach to this dressing is to simply place a defibrillator pad on the wound. Although it doesn’t allow for escape of pleural air, the pad’s adhesive resolves the problems of too much time needed to tape three sides of the dressing and failure of the adhesive to stick to the patient’s chest wall. In some tactical settings, this simple approach combined with repeated needle decompression or occasionally “burping” the dressing, is preferred over the other dressing types. (emphasis added)

The authors here note that unlike the front-line TCCC recommendation of a vented chest seal, a defibrillator pad will not allow for the escape of air and should be considered a fully occlusive dressing. Emergency Medical Procedures published by McGraw Hill in the Open Chest Wound Management section notes:[4]

The supplies for an occlusive dressing (i.e., petrolatum gauze) may not be readily available within or outside of the Emergency Department. Numerous substitutes for the petrolatum gauze are available. This includes a defibrillator pad. These gel-like pads are large, can be cut to size, and adhere to both dry and wet skin. (emphasis added)

Fire Engineering published an educational video titled EMS: Sucking Chest Wound in which they recommended this technique that can be found here.[5] EMS World also mentioned this use in Quality Corner: Ambulance Supplies for the 21st Century, briefly noting:[6]

Defibrillation pads can double as a chest seal in a pinch.

It seems clear that the application of a defibrillator pad as a fully occlusive dressing is a somewhat well known off-label use.

The How To

Using a defibrillator pad as a chest seal is a relatively easy task, as defibrillator pads are already designed to adhere to the thorax. The provider simply needs to place the defibrillator pad over the site of injury, just as they initially did with their gloved hand (preferably during the patients maximal exhalation).[8] That being said, there are some nuances to consider.

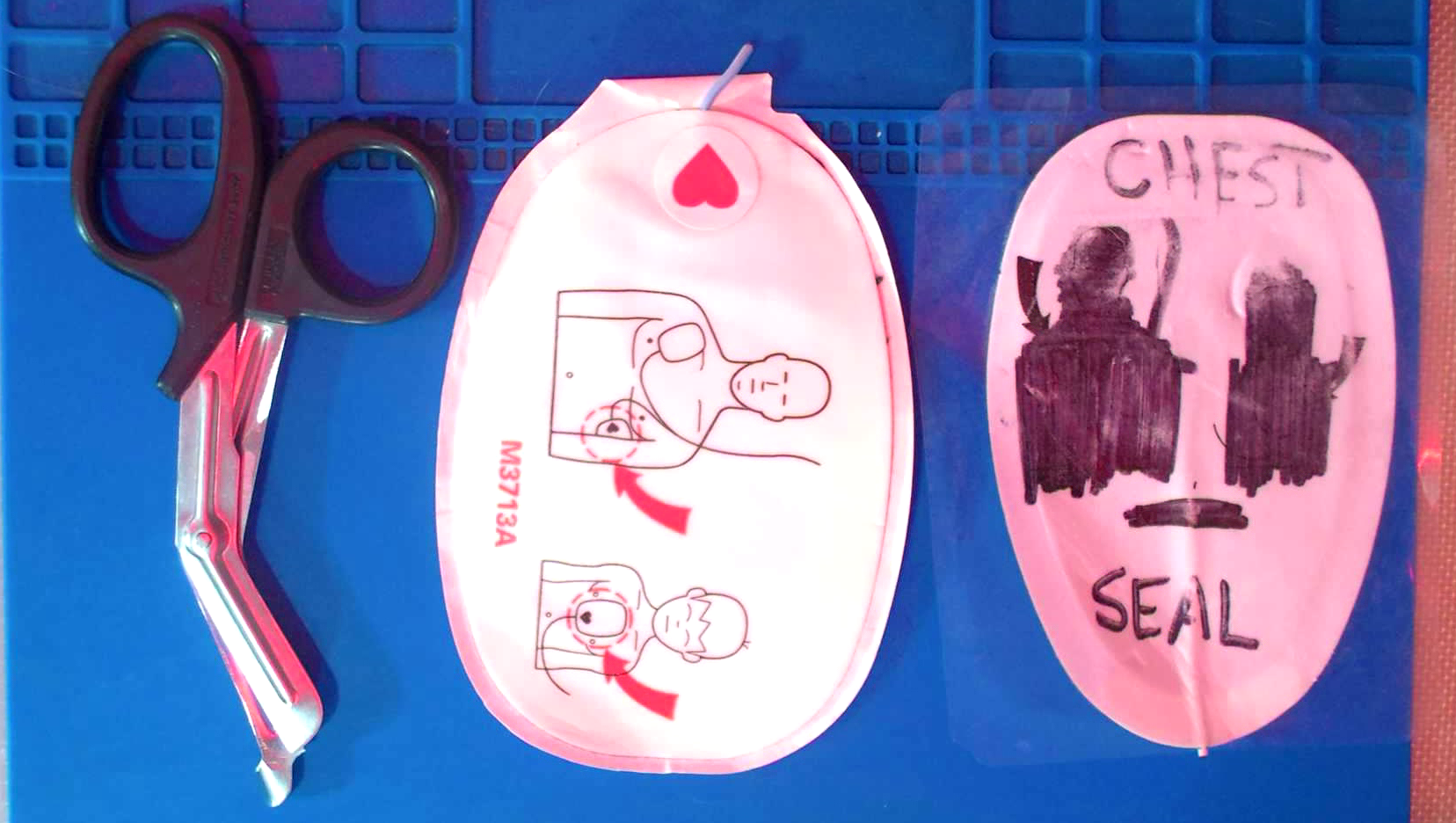

Communication

Anything a professional rescuer does that is unusual requires excellent communication with the healthcare team. A provider should go out of their way to explain the use of a defibrillator pad as a chest seal to the rest of the team at the time and front-load their turnover report with the off-label use. Once applied to the patients thorax, a defibrillation pad is likely to be assumed by other professionals to be there for defibrillation, not as a chest seal. If not communicated clearly, a receiving team may remove the pad with the intent to place defibrillator electrodes compatible with their equipment. To avoid this, a defibrillator pad can be prepared by cutting off the electrode wires and crossing out the placement instructions. Furthermore, writing "CHEST SEAL" in marker on the pad can help label what it is being used for at the time.

Application

There are no special concerns when using a defibrillation pad as a chest seal. Protocols and guidelines should be followed for a non-vented chest seal or fully occlusive dressing. While a vented chest seal remains the gold-standard treatment, when not available, a fully occlusive dressing (non-vented chest seal) is the second-line recommendation.[2, 7] All fully occlusive dressings applied to penetrating thoracic trauma require careful monitoring for the development of tension pneumothorax and may require "burping" or concurrent needle decompression or chest tube insertion.[2,4,8] All of these considerations remain the same with off-label use of a defibrillation pad or a purpose-built non-vented chest seal. Both qualify as fully occlusive dressings and protocols should be followed as such.

Conclusion

Off-label use of any piece of medical equipment rarely comes with large data sets and studies; however, the practice and experience of professional rescuers has proven this to be a useful tactic. Until widespread adoption and standardization of vented chest seals across civilian EMS is a reality, those providers left to improvise dressings with occlusive materials and tape can use this technique as a faster, easier, and more effective way to seal a communicating chest wound.

- Koch BW, Howell DM, Kahwaji CI. EMS Pneumothorax. [Updated 2022 Sep 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov | archive.org

- Anonymous A. Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines for Medical Personnel 15 December 2021. J Spec Oper Med. 2022 Spring;22(1):11-17. doi: 10.55460/ETZI-SI9T. PMID: 35278312. Available at: books.allogy.com | archive.org

- Gilmore W, Rathert N. Treating Sucking Chest Wounds and Other Traumatic Chest Injuries 19 July 2013. Journal of Emergency Medical Services [online]. Available at: jems.com | archive.org

- Chapter 41. Open Chest Wound Management. In: Reichman EF. eds. Emergency Medicine Procedures, 2e. McGraw Hill; 2013. Accessed January 06, 2023. Available at: accessemergencymedicine.mhmedical.com | archive.org

- McEvoy M. EMS: Sucking Chest Wound #1408226065001 03 Nov. 2020. Fire Engineering. Available at: youtube.com

- Hayes J. Quality Corner: Ambulance Supplies for the 21st Century 05 Nov. 2015. EMS World Online. Available at: hmpgloballearningnetwork.com | archive.org

- Kheirabadi BS, Terrazas IB, Koller A, Allen PB, Klemcke HG, Convertino VA, Dubick MA, Gerhardt RT, Blackbourne LH. Vented versus unvented chest seals for treatment of pneumothorax and prevention of tension pneumothorax in a swine model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Jul;75(1):150-6. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e3182988afe. PMID: 23940861. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov | archive.org

- Chapter 10. Trauma. In: Pollak NA, McEvoy M, et al. Critical Care Transport 2022. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS).